3x365days of gratitude

PhD diary is one where everything writes itself. All were generated from maximum ambition, maximum audacity, and perhaps programmatic disobedience to explore a new thing, to understand where I come from. This was a three-year Myanmar case study PhD, but I spent more than a decade of effort to generate it. When it ended it was empty, and at the same time never empty but filling with gratitude and gratefulness, and then I realise many more to continue. This solo experience was abstract but became a product because of the support from a group of people – the best supervisor, amazing internal assessor and external examiner, unconditional love and support from family and relatives, SRB (Sustainable Research Building) friends, and friends from Myanmar and Singapore.

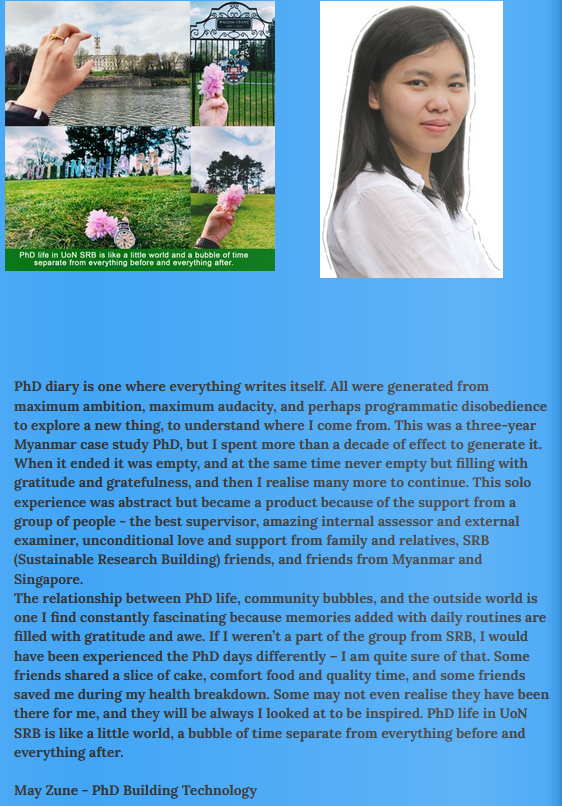

The relationship between PhD life, community bubbles, and the outside world is one I find constantly fascinating because memories added to daily routines are filled with gratitude and awe. If I weren’t a part of the group from SRB, I would have experienced the PhD days differently – I am quite sure of that. Some friends shared a slice of cake, comfort food and quality time, and some friends saved me during my health breakdown. Some may not even realise they have been there for me, and they will be always looked at to be inspired. PhD life in UoN SRB is like a little world, a bubble of time separate from everything before and everything after.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the amazing supervisors Prof Lucelia Rodrigues and Prof Mark Gillott, the internal assessor Dr Robin Wilson, external examiners Dr Anna Mavrogianni from the Bartlett UCL. Thank you for giving me this experience.

The traditional graduation was postponed due to the covid19 pandemic. On the 4th of August 2021, the UON , Faculty of Engineering created a beautiful graduation year book for “the Graduation without borders 2021“. This gives me the idea to record this amazing experience on my blog.

I need to do two years restriction for my thesis “Improving The Thermal Performance And Resilience Of Myanmar Housing In A Changing Climate”, which was submitted to the University of Nottingham, due to the embargo period of publications. But here is the abstract and postscript, and I will update a downloadable link of the thesis when it is available to share publicly.

Image courtesy of Hkun Lat (permission obtained from the photographer)

This photograph displays a Buddhist temple occupying one half of a mountain, while the other has been entirely carved away by heavy machinery mining for jade, in Hpakant, Kachin State, Myanmar (Lat, 2021). The location of this picture is just 150km away from Myitkyina, one of the case study cities in this thesis. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this picture tells many unwritten stories of inequality, climate change, deforestation, complete disregard for human values in an unsustainable business-as-usual program, corruption, and never-ending civil wars of Myanmar: an unfinished nation at the heart of 21st century Asia, between India and China.

Abstract

Despite the long-term climate risk index for the period 1990-2018, there is a dearth of research and understanding of the vulnerability of homes to overheating in Myanmar. This thesis adopted a “case study research method with multiple cases” and addressed concerns about climate change impacts on Myanmar housing, particularly for the thermal performance of detached houses, which comprise the primary housing type in Myanmar. In order to fill the research gap in Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan and the Myanmar Building Code, four objectives were structured for the scope of this thesis: (1) lessons learnt from Myanmar vernacular architecture; (2) an investigation of the impacts of climate change and overheating risks in Myanmar housing; (3) an investigation of the impacts of the Passivhaus’ fabric-first approach on the Myanmar contexts; and (4) a review of barriers, challenges, and limitations of adopting the Passivhaus’ fabric-first approach in Myanmar.

Changes in the use of building envelope materials were the focus of simulation case studies comparing vernacular materials and their customs in building modern materials; the results showed that vernacular houses would not be sufficient to achieve thermal comfort in the predicted future climate scenario RCP 8.5 as the efficacy of passive design techniques has decreased. The results of field case studies generated from a one-year-long monitored data set for a vernacular dwelling and a modern dwelling in Myanmar showed that both dwellings did not give an adequate performance to meet thermal comfort requirements throughout the year. The vernacular dwelling in the Koppen climate Cwa maintained wet-bulb temperature below 30°C when the outdoor weather had 8.5% of the annual hours above wet-bulb temperature 30°C. The modern dwelling in the Koppen climate Aw maintained 48.5% of the annual hour below wet-bulb temperature 30°C when its outdoor weather had 51% of the annual hour below wet-bulb temperature 30°C.

In order to determine the Passivhaus concept in an adaptive thermal comfort model of Myanmar housing, it was hypothesised that a slightly higher U-value for wall and floor could be more effective in Myanmar climates than the very low U-value suggested by the Passivhaus standard; the simulation results revealed that the hypothesis could be sufficient to achieve Passivhaus targets if the synergistic effects between shading and building envelope design were considered. It was also found that if the roof has a cool roof effect, “the higher the u-value, the better” could overwrite “the lower the u-value, the better,” which is a characteristic of reflective insulation. Furthermore, it could meet the requirements to reduce building self-weight for the earthquake resistance design in Myanmar. However, it was also found that the Passivhaus scenario maintained a higher percentage of the annual hour for high heat index and wet-bulb temperatures than the partially Passivhaus scenario in the studied dwellings if no mechanical ventilation was considered.

The results of this research support the hypothesis, revealing that Passivhaus building envelope parameters and optimum variables can improve the tropical building thermal envelope of the studied climate in future climate change scenarios. Fabric-first variable case studies were particularly relevant given the vulnerability of homes to overheating in Myanmar, and the implications of the findings offer directions for more effective good practice and guidance for Passivhaus construction in Myanmar’s tropical context.

Postscript

The thesis was developed in 2016, just a year after the 2015 Myanmar general election, as a long period of isolation was officially ended. The focus of this thesis was to improve the thermal performance and resilience of Myanmar housing in a changing climate as the author strongly believe that the devastating impacts of climate change will not allow Myanmar to isolate politically. Using a case-study research method, empirical and quantitative assessments were presented. Whilst measurable data sets were demonstrated in this thesis using predicted future climate change scenarios, and it is also important to know that the living history of Myanmar will change any prediction of the future of the country.

Myanmar, a pariah state that had sealed itself off from the world until reopening in 2011, is resembling a bygone style of autocracy in 2021 (Fisher, 2021). On the 1st of February 2021, 50 million Myanmar people found that ten years of democratic progress in Myanmar are at risk after the 2021 Myanmar coup d’état. It was the day the doors of Myanmar opened to a very different future. Although it is difficult to see how things will play out over the coming weeks and months, as the Myanmar coup was meant to be a conservative reset, the coming months will probably see continuing strikes, heightened repression, violent resistance, and an agonising descent into needless poverty (Myint-U, 2021b). At the time of submitting this thesis, Myanmar is on the brink of state failure again, and the country remains ungovernable in 2021.

Selected international indices of the World Bank for 2010 (before the military rule ended) and 2020 showed that despite improvements in measures like corruption and democratic structures, the country remained in an extremely vulnerable situation (Buchholz, 2021). Just a few weeks after the military coup, on February 25, several local people reported that there was illegal logging of Ahlaungdaw Kathapha National Park in Sagaing Region, although the civilian government of Myanmar banned the export of raw logs of all species in 2014 (Forestlegality, 2016). Likewise, the World Bank announced a forecast that Myanmar’s economy is expected to contract by 10% in 2021, despite a sharp reversal from the previous prediction of 5.9% growth in October 2020. This is the most devastating collapse since 1988 (Reuters, 2021). A briefing to the UN Security Council’s 9 April 2021 clearly said that (i) the banking system is at a virtual standstill in Myanmar, (ii) supply chains are breaking down, (iii) the health system has collapsed, (iv) armed conflict is rising, and (iv) much of Myanmar’s natural wealth is in the hands of unregulated actors (Horsey, 2021). Furthermore, the 2021 Myanmar coup d’état reveals that what has changed in Myanmar and what has not, and will also alter the country’s future for all of its peoples.

Ethnicity is one of the primary lenses through which many scholars view conflict in Burma/Myanmar. It is important to understand the ‘Wages of Burman-ness’ and Burman privilege in contemporary Myanmar, whereby Burman-ness can be conceptualised as a form of institutionalised dominance, similar to Whiteness in many Western cultures (Walton, 2013). On the other hand, the internal conflict in Myanmar has primarily been ethnic-based since independence in 1948; an array of ethnic political movements and their armed wings have sought political, economic, cultural, and social rights as protection against domination by (majority) Burman authorities. Eventually, some kind of revolution must come without returning to the past (military era). For which, the movement of democracy alone is not enough. There needs to be a more progressive agenda for change, across ethnic lines, towards a fairer as well as freer society for all of Myanmar’s peoples (Myint-U, 2021b). In this respect, understanding the culture of different Myanmar ethnicity is essential to develop different housing program for the diverse cultural and local context.

In the other study by the author, an enquiry was developed into the way homes in Myanmar manifest their culture and local contexts and traced changes from the archetypal safeguarding of occupants to more sophisticated modern-day concerns relating to resilience and safety, particularly about the way climate change and socio-political scenarios impacted in the making of homes (Zune et al., 2020a). The argument was developed using two methods: maps and narrative method and travel story narrative method.

For the map and narrative method, an observational analysis of eight Myanmar vernacular houses was a starting point, which are replicas of significant symbolic structures characteristic of the major ethnicities residing in the country. That vernacular study was partly presented in this thesis Chapter 1. The “maps and narrative” method was used to tell different stories about different house types in Myanmar within their climate, culture, and location settings and their influence on passive vernacular design for comfort and room configurations. They discoursed on how the human settlement historically developed and outlined the ways in which communities have made their homes, in terms of establishing vernacular practices, arranging room configurations and reflecting the given and changing climate and cultural contexts. The “maps and narrative” method (Ryan et al., 2016) supports the discussion of different stories associated with a map in different times and also allows the author to push forward the changing context in the making of homes in different locations.

Secondly, the author drew learnings from a “travel story narrative” exercise that followed video documentaries covering homes of the 21st century and beyond, referring to two videos originally aired as “Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown” by CNN (Bourdain, 2013) and “Burma with Simon Reeve” by BBC (Reeve, 2018). Bourdain is a world-renowned chef, bestselling author, and multiple Emmy-winning television personalities; his programme is epitomised by the opening referring to Myanmar: “After 50 years of nightmare, something unexpected is happening here, and it’s pretty incredible”. Reeve is a British author and television presenter, and his documentary explored the country’s both rich culture and controversial experiences. Five years after Bourdain’s visit to Myanmar, Reeve found that Myanmar is “still a place of tragedy”. Documentary film has long been associated with travel and culture, and it can also provide the stories that make film-induced tourism so compelling while simultaneously providing a more human look at the area (Mecham, 2015).

The juxtaposition of these two narratives led the author to the suggestion that over the course of time, some things remain eternal in the making of homes, which are as true in Myanmar today as in vernacular homes of centuries ago, yet something must change to make homes, neighbourhoods, and cities safe and resilient to the global threats of climate change – just as vernacular architecture achieved such safety for local threats – keeping within the requirements and traditions of Myanmar people. The author argued that everything has changed in Myanmar homes’ design, delivery and occupation, yet something must change in the near future in order to ensure homes are fit for purpose and climate change adaptation.

Considering the political crisis in Myanmar in 2021, every research-related action for Myanmar sustainable development plan and resilient housing has to accommodate a better understanding of the country’s unstable economy and policy, inequity among ethnic groups, economic inequality, and the country’s unique political economy as it has emerged since 1988, across a landscape dominated by both state and non-state armed groups. All those considerations would more or less affect the future research discussed in this thesis and the development of the country. It also means a qualitative change in what people do and the institutions in which they work. In this way, development entails a remaking of society (Myint-U, 2020). To realise the Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan (MSDP, 2018), Myanmar needs to reimagine its economic future with a new kind of democracy (Myint-U, 2021a). A reasonable housing policy may be developed with a dictatorship; however, climate change has already led to the migration of millions in Myanmar; the cyclone Nargis in 2008 was a piece of unchangeable evidence. A desperately poor and unequal country at war with itself will not produce anything other than a facade of democracy.

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges collectively facing the world today. There are two components to respond to the challenge posed by climate change: addressing the causes of climate change by reducing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – mitigation and preparing for the consequences – adaptation. Strong national and international actions are required to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and building resilient communities; particularly, the legislative, executive and judicial branches all have a role to play. Understandably, it is a challenge for Myanmar to achieve climate change adaptation unless all the authorities and government sectors collectively consider each activity related to climate change.

After two months of the military coup, at the time of submitting this thesis, no one could have imagined where Myanmar would still be in 2021. Nevertheless, climate change impacts are already affecting ecological and socio-economic systems, and it is anticipated that these impacts will continue well into the future. A solid basis for adaptation planning, implementation, monitoring and evaluation, targeting present and future climate change risks pertaining to Myanmar housing for different climate zones and different ethnic groups, will be possible if the people of Myanmar craft together a progressive agenda across ethnic lines, centred on equality and development as well as peace and justice.